With war looming, press coverage of gambling at the

beginning of the 1940s waned. However, gambling operations continued. In

December 1940, Hamilton County Sheriff Fred Sperber’s office destroyed 50 slot

machines they had seized. In early 1942, the Internal Revenue Bureau released a

list of 250 Hamilton County business owners who purchased a tax stamp for slot

machines or other gambling devices. Speculation was that gambling device

owners were under the misapprehension that purchasing a tax stamp might prevent

seizure by local law enforcement. Cincinnati Police said that only 19 of the

machines on the list were located within the city. The Sheriff’s Office said

they had found no devices used for gambling and all were clearly marked “for

amusement only.”

In the spring of 1943, there was renewed interest in

cracking down on gambling in the area. Cincinnati city solicitor John Ellis

and Hamilton County prosecutor Carson Hoy announced that they would work

together to enforce anti-gambling laws, in particular the numbers racket. The

new sheriff, Republican C. Taylor Handman, gave the same tired line that previous sheriffs had given: His deputies would enforce anti-gambling laws if

they found any infractions, but that local authorities were responsible for

enforcing the law in their own municipalities.

A few days later, though, Handman announced an

anti-gambling campaign with a new target – bingo. Was this a genuine attempt to

eradicate the evils of bingo or a ploy to divert citizens, the press, and

politicians from law enforcement's inability to crack down on more serious gambling violations? Archbishop John McNicholas called

out the hypocrisy of officials who were overlooking worse offenses and complained

that no distinction was being made between innocent games of chance and games of chance

that harmed people.

A few days later, the sheriff announced that his

department had found no gambling in unincorporated areas of the county and received

100 percent cooperation with his anti-bingo and anti-gambling campaign. He did

caution, though, that there might be some hidden gambling operations. I believe gamblers would say that he was hedging his bets.

Within three weeks, the Cincinnati Post discovered that

at least three Elmwood Place establishments were taking bets on horse races. Interestingly,

Sheriff Handman said there was no gambling in Elmwood Place and authorities

there concurred.

In June 1944, at the request of the grand jury, Sheriff

Handman and his deputies raided a bookmaking operation in St. Bernard. They

disconnected eight telephone lines there, but no arrests were made because

there was no one on the premises. Cincinnati city councilmen Albert Cash and

Russell Wilson pulled no punches. Cash asked the grand jury to investigate who was

being bribed to protect gambling operations in Hamilton County. Wilson urged

Handman to investigate Elmwood Place and St. Bernard. Handman gave the same old

response that he couldn’t enforce the law in incorporated areas unless local

authorities requested his help. Wilson said that Handman could enforce the law

anywhere in the county, but didn’t do so because his “bosses,” gamblers with

connections to the Republican party, wouldn’t allow him to do so.

The following day, Handman’s deputies seized 50 slot

machines in raids. A day later, he asserted that unincorporated areas of the

county were free from gambling. He also addressed Cash’s and Wilson’s

allegations that someone had tipped off a bookmaking operation of the raid in

St. Bernard. He said he couldn’t have tipped anyone off because he had been

with a grand jury representative from the time of the grand jury’s directive

until the time of the raid.

In July 1944, gambling operations in Fairfax and Elmwood Place

inexplicably shut down. Sheriff Handman said he hadn’t issued any special

orders and was perplexed about the closures. He said that gambling in the

county was “closed down tighter than I ever heard of it being before.” Despite

this statement, Russell Wilson criticized Handman, saying that if he was unable

to control gambling in incorporated areas of the county, he could at least

enforce the law in Fairfax.

Several weeks later, word was out that bookie joints in

Fairfax and Elmwood Place were once again open for business. It had been

expected that the gambling establishments would remain closed until after the

November 1944 election. It wasn’t clear how the bookmaking establishments knew

that “the heat was off.” Cincinnati gambling establishments were also

operating, but on the low down. They wouldn’t take bets from strangers, which

hampered the efforts of Cincinnati undercover police officers.

Russell Wilson continued his attacks on Sheriff Handman

and Prosecutor Hoy, suggesting that they were both under the control of

gamblers. Handman’s position had been that local authorities were responsible for

enforcing the law in their own communities. However, Wilson pointed to a recent

case in Cuyahoga County, Ohio in which the court ruled that county sheriffs

have shared responsibility with municipal authorities for enforcing the law. By

the fall, Sheriff Handman announced that due to his department’s efforts,

gambling was once again shut down in the county, including in hotspots like

Elmwood Place, Norwood, and Fairfax. Prosecutor Hoy said

that he would investigate the allegations of corruption of public officials by

gambling operators.

In a speech, Russell Wilson challenged Handman, Hoy, and

Republican political leadership to permanently shut down gambling in the

county. He again suggested that officials might be on the take. Prosecutor Hoy then announced an “all-out war on

gambling” with the cooperation of Sheriff Handman. He said the intent was to permanently

shut down gambling operations in Hamilton County. Would anyone care to guess

how that worked out?

For the next few years, the pattern seemed to continue.

Authorities would claim that open gambling had ceased, followed shortly

thereafter by reports that it hadn’t. There were allegations of incompetence at

best and corruption at worst of county and local officials.

Things took a turn for the worse in mid to late 1947. In

August, Sheriff Handman reported that he had learned of an armed robbery at the

Lake Louise Tavern in Anderson Township. It wasn’t reported “officially,” but

he learned of it from a press report. Two gunmen lined patrons against a wall

and made off with $2,000 in cash and jewelry. Handman said it was “a sad state

of affairs” when this type of crime wasn’t reported to authorities.

Around the same time, Norwood’s mayor reported that five “hoodlums”

had thrown a 15-pound rock at the front of his house. Prosecutor Hoy had recently

requested that the grand jury conduct an investigation into gambling in Norwood

and subpoenas for 13 witnesses had been issued.

But the most troubling of the incidents occurred November

19, 1947 in Fairfax. One newspaper stated that the robbery was at the Fairfax Tavern (where the pony keg and Baker's Pub once were) and another at the Fairfax Club (which was in a building behind the tavern, where the Church of God was later located). I haven't yet determined the relationship between these two establishments, other than there was gambling at both. Newspaper articles reported on a location "in the rear" of Fairfax Tavern, so it is unclear whether the robbery occurred within the tavern itself or in the building behind the tavern. Although it appears that there was gambling in some form at Fairfax Tavern, that the robbery and a lot of the gambling action were most likely at the Fairfax Club.

In any event, three armed robbers

lined 25 patrons against a wall. The gunmen made off with between $1,500 and

$7,000 in cash and jewelry and a Fairfax man, George Hykle, sustained minor injuries when he attempted to disarm a gunman.

Two Hamilton County deputies responding to a nearby traffic accident received the robbery call. The deputies saw three men running across

the Fairfax Club parking lot, heading toward Lonsdale. The robbers opened

fire on the deputies and the deputies returned fire. The getaway car was parked

on Lonsdale, but the robbers were not able to get to it during the shootout. Instead, they ran

behind the businesses on Wooster Pike, heading toward Watterson, to escape. Two

of the suspects carjacked a Mariemont man at the corner of Wooster and

Watterson and made him drive them to downtown Cincinnati. Prosecutor Hoy and

Sheriff Handman said the Fairfax Club had been under surveillance, but because

their undercover officers were not known in the neighborhood, they weren’t

permitted to place any bets.

After the search for the robbers, police returned to the Fairfax Club and found no one there except a porter. The abandoned getaway car was later determined to have been stolen in Hamilton, Ohio.

The following day, the Cincinnati Post published an

editorial critical of Sheriff Handman, stating that his failure to crack down

on bookmaking operations could cost someone their life in the robbery of a

gambling establishment.

After the robbery at the Fairfax Club, county police

reported that they were told that the Club was run by a man named Edward

Ziegler, but had previously been run by Ike Hyams. This was the first formal

mention of Ike Hyams as being involved in the Fairfax gambling scene.

Ike Hyams was born in the West End in Cincinnati. In 1919

he became a “commission broker” or “sportsman,” as he preferred to be called,

or a bookie, as most other people called him. He was also deeply involved in

Republican politics. He moved to Price Hill, where he and his wife Lena raised

their family. Ike ran the gambling operations in Elmwood Place and was the major player in Hamilton County bookmaking, known as "king of the bookies." One might think that Ike would have

had a lot of unpleasant run-ins with Elmwood Place officials. Run-ins, yes;

unpleasant, apparently not. Here is a picture of a smiling Elmwood Place police chief

serving Ike with a warrant in 1949:

From the Cincinnati Post, April 25, 1984

So, Ike Hyams' involvement in Fairfax

bookmaking operations shows how lucrative gambling was in Fairfax. At the time of the 1947 robbery, Ike didn't own the Fairfax Club property, but his wife Lena later purchased it in December 1950.

A month after the Fairfax Club robbery, Sheriff C. Taylor

Handman announced that he would not be running for reelection the following

year, presumably because of the criticism he received about being unable to

handle the gambling problem in Hamilton County. In an editorial, the Cincinnati

Enquirer stated that they didn’t think Handman had been bribed, but that he

wasn’t thick-skinned enough for the job and would likely be happier out of the

public eye.

Although the Fairfax Tavern and Fairfax Club seemed to receive most

of the gambling news coverage in those days, let us not forget Kruse’s Smoke

Shop less than a block away. In July 1948, Kruse’s proprietor and Fairfax

resident Clarence Kruse had a heart attack at the business he had owned for 18

years and passed away at the age of 53. The news article announcing his death

stated, “he was widely known in sporting circles in the eastern area of the

county.” His son Jim took over the operation.

In addition to bookmaking, slot machines and other

gambling devices were still operating in Fairfax, and not just in the expected

spots. The 1947 and 1948 Internal Revenue tax stamp lists included the Fairfax

Club, Fairfax Pharmacy, Gulf Service Station, Kream Kottage, White’s Restaurant,

and even Frisch’s Mainliner.

In late 1948, state liquor investigators joined the

anti-gambling efforts in Hamilton County. Also, there was a new sheriff in

town. In November, Democrat Dan Tehan was elected. He said that he was against

slot machines and syndicated gambling, but that it would be nearly impossible

to eliminate them.

After being shut down prior to the election, slot

machines made a comeback in the county in late November. Both liquor

enforcement officials and Sheriff Handman expressed their shock, but vowed to

investigate. The Cincinnati Post reported that they had no problem finding a

variety of slot machines and gambling devices. One café owner reported that the

slot machines would be in operation for the next 40 days, until Dan Tehan took

office.

When Tehan took office, he promised to study the gambling

problem and said that his enforcement of anti-gambling laws would “speak for

itself.” Prosecutor Hoy vowed to cooperate with Tehan’s efforts. Tehan didn’t

announce when or if gambling raids would begin, but there was a report that one

Fairfax establishment with an extensive bookmaking operation had inexplicably closed.

Tehan said the closure occurred without his knowledge and that as far as he

knew all slot machines in the county had shut down. Prosecutor Hoy confirmed

this when he announced that an undercover investigation by his office revealed

that slot machines in the county had disappeared.

Moving into the county around this time was a new chief

of the State Liquor Control Department for the Cincinnati area, Frank Acton. Liquor

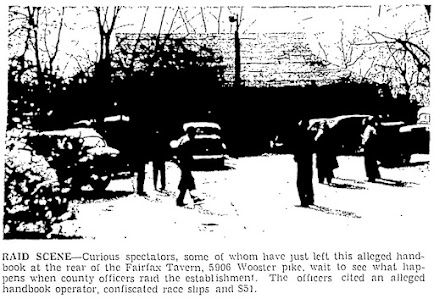

control agents wasted no time in initiating raids. In late March 1949, the

Sheriff’s Office and state liquor enforcement agents raided several Hamilton

County gambling establishments, including Kruse's Smoke Shop and "the rear of" Fairfax Tavern. 50 people were at the Tavern (or Club) at the time of the raid and

Fairfax resident Clifford Tekulve was cited for operating a game of chance. He

later pleaded guilty and was fined $100 plus costs. There were 25 people at

Kruse’s when they were raided and Jim Kruse was cited.

From the Cincinnati Post, March 29, 1949

It

didn’t take Acton long to accuse the Sheriff’s Office of tipping off gambling

operators to planned raids. The grand jury investigated,

but found no evidence to support this allegation. The grand jury did direct the

Sheriff’s Office and Liquor Control agents to cooperate with one another. Tehan

and Acton met to develop a strategy and vowed to coordinate efforts. Acton even

took on the Elmwood Place gambling establishments and arrested Ike Hyams’ son,

though Elmwood Place officials later dropped the charges against him.

The Sheriff’s Office and Liquor Control agents raided the

Fairfax Tavern twice in May 1949. Officers said that the bookmaking operation

was going “full blast” at the time of the second raid. Cliff Tekulve was again

cited for operating a game of chance. Liquor Control agents cited the owners of

Fairfax Tavern, Susan and Frank Brockamp, for violating their liquor permit by

allowing gambling on the premises.

If the annual tax stamp list was any indication, slot

machines might have been on the downturn. Only 26 tax stamps were purchased in

Hamilton County in 1949. Through the years, though, slot machine owners had

learned that the tax stamps didn’t prevent seizure by law enforcement and may

have just stopped purchasing the stamps. Also, there had been more persistent and

consistent raids that might have forced proprietors to move gambling devices

into hiding.

Liquor Control agents and Sheriff’s deputies continued

raids throughout the county. However, Frank Acton, the aggressive, no-nonsense state

Liquor Control agent who had accused other officials of improprieties, was

transferred from Cincinnati after he was seen at Churchill Downs as the guest

of a local tavern owner.

In the spring of 1950, something happened nationally that

stoked anti-gambling sentiment in citizens who hadn’t previously been

bothered by gambling in their communities. In 1949, the American Municipal

Association had asked the federal government to investigate the growth of organized

crime. Senator Estes Kefauver introduced a resolution to create a special

committee, which became known informally as the Kefauver Committee. The focus

became what Kefauver called “the life blood of organized crime,” gambling. Over

15 months, the committee held hearings in 14 cities and interviewed hundreds of

witnesses. Many of the committee’s proceedings were broadcast live and became

quite popular. The hearings revealed to average Americans the role of organized

crime in gambling operations and the influence crime syndicates and gambling

rings had on elected officials. Though the committee didn’t achieve much in

terms of federal legislation, citizens following the committee’s work began

pressuring their local authorities to crack down on gambling in their communities.

While the Kefauver hearings were going on, gambling

operations and anti-gambling raids continued in Fairfax and Hamilton County.

Frank and Susan Brockamp, owners of the Fairfax Tavern, appeared before the

State Liquor Board to answer a charge that they had gambling devices on

premises. The state suspended their liquor license for 30 days.

A March 1951 article in the Cincinnati Post reported that

there were 200 bookmaking establishments in the county that took in

approximately 10 million dollars a year. Most of these bookie joints weren’t

the “fancy emporia” found in Fairfax and Elmwood Place. (The Cincinnati Times Star said that Fairfax had one of the "swankiest" establishments in the area.) The Post reported that

there were few bookmaking operations in unincorporated areas because the

Sheriff’s Office handled law enforcement there. Fairfax was obviously the exception.

By April, wire and telephone service to bookmaking

operations had been suspended in some major Ohio cities. Wire and telephone

service to the Fairfax bookie joints, though, was still active and in use. Sheriff’s

deputies raided three gambling establishments on April 5, but by the time they got to the Fairfax establishments, the gambling operations were closed down.

By June, Sheriff Tehan said there were reports that

bookies were again operating in Fairfax. He said that deputies were in Fairfax

a few days earlier and didn’t find anything, so if there was gambling it was on

the sly. He said it would be difficult for undercover deputies to place a bet

and make an arrest under those circumstances.

Just as suddenly as Fairfax began making gambling news,

it dropped out of it. June 1951 was the last mention I found in local

newspapers about gambling in Fairfax. In 1953, Ike Hyams was trying to sell or lease his Fairfax property; he was abandoning bookmaking and opening a furniture store. Fairfax became incorporated in 1955 and

the new village formed its own police department, which must have been a huge

relief to the Sheriff’s Department. The new village was seeking a municipal building and briefly considered both the former Kruse's and Fairfax Club locations.

There have been a number of changes in Ohio gambling laws

since those days. Charitable bingo games, raffles, and the like are legal as

long as all profits go to the organization. In 1973, the Ohio Lottery was introduced.

Gambling devices like slot machines are still illegal, except in the four

casinos authorized in Cincinnati, Cleveland, Columbus, and Toledo. Sports

betting was legalized in Ohio in late 2021 and sportsbooks are expected to

launch here on January 1, 2023.

Sources available upon request.