Several months ago, I read a social media rant by a Fairfax

resident who was critical of the community because of a crime of which she was

a victim. I am always perplexed by people who believe that there are communities

that are completely wholesome, idyllic, and crime-free. Fairfax is a pretty safe

place with a lot of good things going for it, but has never, ever been

crime-free.

In previous posts I have covered some of our community’s

more high-profile crimes. (See The Service Station Murder, The Gambling Scene

Part 1 and Part 2, and The Police Shootout.) However, throughout its history,

crime in Fairfax has run the gamut. There was moonshining during Prohibition. There

have been robberies and burglaries at businesses like Yochum’s Grocery,

Atwood’s Pharmacy, and King Kwik. There were break-ins at Fairfax School and

even a couple in the 1970s at the police station. And there was a particularly

distressing kidnapping and murder of an innocent child that will be covered in

an article later this year. Domestic violence, assault, vandalism, murder; it has

all happened here.

Fairfax is a nice community, but it wasn’t even crime-free in

the “good old days” when these crimes, a few of the more newsworthy ones in our

history, occurred:

The Lillie Hammond Homicide

In April 1930, 19-year-old Lillie Hammond and her

28-year-old husband William Barker Hammond were renting a home on Eleanor

Street, where they lived with their nine-month-old son Stanley. They were

expecting a second child and soon relocated to a home on Southern Avenue near

Wooster Pike.

On August 8, 1930, the pregnant Lillie Hammond was killed

by a gunshot to the head, fired by her husband Barker.

Barker’s story was that after work that day, he went to

town for a shave and haircut. He arrived home at around 10:30 p.m. and Lillie

prepared a meal for him. They went to their bedroom and prepared to go to bed.

There was an old revolver on the dresser and he said to her, “I wonder if this

old gun would shoot.” He said the gun discharged as he was handling it and that

the shooting was accidental.

The Hammonds’ neighbors notified the Hamilton County

Sheriff’s Department, while Barker, inexplicably, went to his brother

Lawrence’s home in Newtown. When Barker returned to his own home, deputies took

him into custody.

August 9, 1930 Cincinnati Times-Star

Lillie’s funeral was on August 10, 1930 and Barker was

permitted to attend in the custody of two deputies. Enroute to the funeral

home, Hammond cried out denials that the shooting was intentional and said that

he had loved his wife. At the funeral home he cried, “What have I done?” and

slumped over the coffin.

The Hamilton County coroner and sheriff weren’t buying

Hammond’s story. They said that the evidence showed that the gun’s trigger had

been pulled twice, but had only fired once. There was also gunpowder in the

wound, indicating that the shot had been fired from close proximity. A Grand

Jury indicted him for second degree murder.

Barker Hammond went to trial in February 1931, still

insisting that the shooting was accidental. Prosecutors argued that the

Hammonds had quarreled and Barker shot Lillie in anger. The first trial ended

in a hung jury.

The case was retried in May 1931 and William Barker

Hammond was convicted of manslaughter. He was sentenced to 10 years in the Ohio

Penitentiary. Hammond’s defense attorney requested that the court either

suspend the sentence or place him on probation, since the shooting was an

accident. The judge denied the request. Barker Hammond served his sentence and

was paroled in September 1942.

The Frank Rogers Ax Attack

35-year-old Frank Rogers and his brother James operated a

wood yard and lived together with their families on Wooster Pike. On the night

of January 26, 1942, James and his wife were out for the evening with another

couple. Frank and his 24-year-old wife Pearl were in bed when there was a knock

on their door. Pearl answered the door to find two men and described the

ensuing scene as follows:

I

didn’t say a word to them, but went in the bedroom and told Frank someone

wanted to see him. The men came in and then said they were going to kill us.

One of them went into the kitchen and got the ax. He kept swinging at Frank and

finally hit him. They kept saying they were going to kill us both. I begged

them to stop.

Pearl was struck on the head with a flashlight and

rendered unconscious. The intruders began firing a .12-gauge shotgun and

.32-gauge pistol owned by James Rogers, shooting out all lights and several

windows. They had cut the telephone lines before they entered the house. They

then tried to set the house on fire by knocking over a lighted lamp. They stole

Mrs. James Rogers’ purse and left in James Rogers’ car. James Rogers and his

wife returned home about 10 minutes after the attack and called the Hamilton

County Sheriff’s Department.

A description of the stolen vehicle was broadcasted and Cincinnati

police located the car and assailants in the West End, even though the car’s license

plates had been changed. The attackers were apprehended and identified as

Willie Cain and Isaac Johnson. Cain was a cousin of the Rogers brothers and had

previously been incarcerated in Kentucky for manslaughter. Johnson had escaped

from a Kentucky jail by sawing through the bars while awaiting transfer to

prison on a robbery conviction. Both Cain and Johnson had worked for the Rogers

brothers.

James Rogers speculated that the attack was actually a

case of mistaken identity because his wife had received an anonymous phone call

weeks earlier threatening her and her husband.

Frank Rogers’ injuries were so severe that he required

several blood transfusions and his leg had to be amputated. He survived,

though, and lived over 30 years more.

Frank Rogers pictured in his hospital bed, January 27, 1942 Cincinnati Post

Cain and Johnson were each charged with two counts of

assault to kill, and one count of grand larceny. Cain pleaded guilty to all

charges. Johnson was found guilty of the assault charges and pleaded guilty to

grand larceny.

There is an interesting twist to this story. It seems

that Pearl wasn’t actually married to Frank Rogers, but at the time of the

attack she was married to two other men. Upon seeing her photo in a

newspaper identified as “Mrs. Pearl Rogers,” her second husband filed for

divorce. During these proceedings, Pearl admitted that she and her first

husband had never divorced and her second husband was granted a divorce.

I’m not sure if a journalist got some facts wrong or I

just watch too much true crime, but there seem to be a few problems with this

story. There some to be some missing pieces. And Pearl? I think authorities needed

to do a deeper dive on that girl.

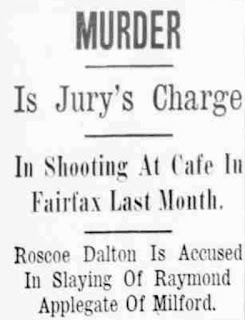

The Raymond Applegate Murder

On the evening of Monday October 15, 1943, 23-year-old

Raymond Applegate was driving around his hometown of Milford, Ohio with his

17-year-old brother-in-law, Roy Miller. They passed two Milford girls, Merle

McFarland and Juanita Bernard, who were looking for a ride to the Cincinnati

bakery where they worked. Applegate had loaned money to a Fairfax man who

frequented Uncle Al’s Grill (where Mac’s Pizza Pub is currently located) and

offered the girls a ride with the intention of stopping at Uncle Al’s to pick

up his money.

While Applegate was inside Uncle Al’s, Merle McFarland

spotted her brother-in-law Roscoe Dalton across the street from the café and

exited the car to speak with him. When Applegate left the café, he approached McFarland

and Dalton saying, “Come on, Merle. You’ll be late for work.” Without saying a

word, Dalton drew a revolver and shot Applegate in the chest.

Applegate was transported to Bethesda Hospital in

critical condition. The bullet had just missed his heart and lodged in his

spinal cord. He was able to give a statement to police about what had

transpired. He said, “I never had a chance . . . I don’t know what it’s all

about.” He said he didn’t know the man who shot him and had never spoken to

him. Raymond Applegate died two days after being shot. He left behind his wife

Mary Catherine and two-year-old and seven-month-old daughters.

Roscoe Dalton’s story didn’t differ significantly from

Applegate’s. Dalton said “[Applegate] was coming toward me. I shot him when he

reached for his pocket.” Dalton said he was carrying a gun because “I expected

some trouble,” though he said he didn’t know Applegate. He said he thought

Applegate was armed. Dalton, a resident of Miami Township in Clermont County,

was married and the father of three small children.

November 18, 1943, Cincinnati Enquirer

Initially, Dalton planned to argue self-defense and

pleaded not guilty. However, he later withdrew his not guilty plea and pleaded

guilty to second degree murder. He was given a life sentence, but was paroled

at some point.

The William Storer Assault

On Saturday March 16, 1946, 11-year-old William Storer

reported that he went to a greenhouse located behind Fairfax School, seeking

summer work there. He was walking through the woods, returning to his home on

Germania, when he encountered four older boys. He recognized the boys, but didn’t

know where they lived or their names, other than that one was called “Whitey.”

William said, "They told me I had no business in the

woods. They tied my hands behind my back and tied my feet in burlap sacks. Then

they tied [me] head down to the tree and set fire to the sacks. Then they ran

away. I kicked and I hollered for help.” That’s right, an 11-year-old Fairfax child

was allegedly hung upside down and set on fire.

William said he was hanging from the tree for around 10

minutes when two Hyde Park girls came to his rescue. The girls were on a hiking

and picnic trip. The girls freed the boy and helped him to the house where he

lived with his grandparents. Neither William,

nor his grandparents, got the girls’ names.

Three days after the attack, the burns on William’s

ankles didn’t seem to be improving. His parents took him to a physician, who

insisted that the attack be reported to the authorities. On March 19, Hamilton

County Sheriff C. Taylor Handman said that his department was investigating the

“Gestapo” methods used in the “torturing by fire” of William Storer. The

following day, three boys aged 13 to 15 admitted to tying the boy to the tree.

They denied setting fire to him, though, saying that he must have set fire to

himself.

William Storer and his grandmother Carrie Beckler

March 19, 1946 Cincinnati Times Star

The boys and their parents were ordered to appear in Juvenile

Court on March 22, 1946. Of course, the story stops abruptly at this point due to

the confidential nature of Juvenile Court proceedings.