Sometimes the news of the world seems so distant from our

experience in Fairfax. Yes, we know there is violent crime; it’s all around us.

However, the really bad stuff seldom touches us as a community. An April 1969

murder disrupted our peaceful way of life.

Troy Lee Carr was a 28-year-old father of two young girls. He and his wife Mary rented a home on Simpson Avenue, which they had moved into in February 1969 because it was close to work and in a nice neighborhood. Troy was employed full-time as a plumbing materials tester at American Standard Company in Mariemont, but also worked part-time as an attendant at Snyder’s Sohio at the corner of Wooster Pike and Simpson. He had worked the day shift at Sohio, but had recently started working the night shift due to the illness of another employee.

On Sunday April 6, 1969, Troy, Mary, and the girls spent the day visiting family in Waynesville, Ohio. After returning home, Troy prepared to begin his 10:00 p.m. shift at Sohio. His part time job was just a couple of blocks from home.

At 4:05 a.m., Mariemont resident Raymond Huber stopped at Snyder’s Sohio on his way to his sales job in Indianapolis. A young man with long hair, a beard, and dressed in black pumped the gas for him. He paid the man, who entered the station to get change. While waiting, Huber noticed a car parked at the side of the station with a person sitting in the passenger side. When the man returned with the change, Huber noticed that the man had blood on him and asked if he had cut himself. The man answered that he had cut himself inside the station.

At 4:20 a.m., two young men from Mount Washington stopped into the station to have a tire repaired. They found Troy Lee Carr in the service station restroom, beaten and clinging to life. The broken cover of a toilet tank was found nearby on the floor. Troy was transported to Our Lady of Mercy Hospital in Mariemont, where he died 85 minutes later. His skull had been fractured and he had cuts on his neck. In addition to his wife and daughters, Troy’s senseless loss was mourned by his parents and eight siblings.

After hearing of the crime on his car radio, Raymond Huber

telephoned Fairfax Police to let them know what he had witnessed earlier that

morning.

Station owner Louis Snyder estimated that $100 had been stolen from Carr. $27 was left in the station’s cash register. Carr’s house and car keys were also missing. Snyder said the station had been open 24 hours, but he would begin closing at night because he was “afraid to ask anyone” to work the overnight shift. He said this was the first time his station had been robbed. Sohio offered a $5,000 reward for information leading to the arrest and conviction of the perpetrator.

Fairfax Police Chief James Finan enlisted the assistance

of the Ohio Bureau of Criminal Investigation and the Cincinnati Police. The BCI

found partial fingerprints at the crime scene, but they were unable to match

them to any prints on file.

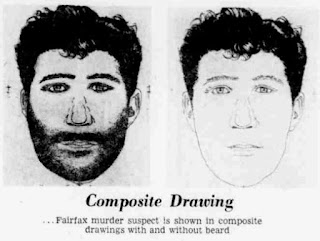

Cincinnati Homicide Specialist Paul Morgan and Fairfax Police Sergeant Paul Ferrara went to Indianapolis to interview the witness who may have encountered the suspect. Raymond Huber helped them make composite renderings of the suspect.

On April 17, Fairfax Police announced that they would have a police artist work with the witness to make refinements to the composite pictures. The composite pictures were made using pre-made facial features that matched the witness description. Chief Finan said the artist rendering should be more detailed and accurate. By this point, police had received over 100 tips but no useful leads.

On July 7, Helton and Mack appeared in Hamilton County Municipal Court. Helton was bound over to the Grand Jury and held without bond. Mack was remanded to the Juvenile Court. Mack was 17 at the time of the crime.

Robert Mack was represented by prominent local defense attorney Bernard Gilday, Jr. Gilday appealed the Juvenile Court’s decision to bind Mack over to the Grand Jury, saying that it violated his constitutional rights. His argument was that Mack didn’t receive a proper hearing before the Juvenile Court prior to Judge Schwartz referring the case to the Grand Jury. On January 20, 1970, the First District Court of Appeals dismissed the first-degree murder charge against Mack and ordered that jurisdiction be returned to Juvenile Court for further proceedings.

While the Mack legal issues were being sorted out, Charles Helton pleaded not guilty to the charge filed against him and was awaiting trial.

On March 20, 1970, Sohio implemented a policy at nearly 150 stations requiring that between 10:00 p.m. and 6:00 a.m., customers would need to pay with exact cash or a credit card. The service station attendant would immediately place cash payments in a safe, to which he wouldn’t have access. Sohio hoped that this would prevent robberies of their stations and bodily harm to their employees.

Charles V. Helton’s trial began on April 28, 1970 before Hamilton County Court of Common Pleas Judge Robert V. Wood. Helton was defended by attorney Henry Sheldon. The prosecution was handled by Assistant Prosecutors Calvin W. Prem, Jr. and Fred J. Cartolano. Judge Wood ruled that a taped statement from Helton, made after his arrest, could be entered into evidence. In this statement, Helton said, "I was drunk and got to thinking. Well, I spent my last money on this gasoline and on this oil and I was completely broke. So, the man walked back into the station and when I went to pay him I forced him into the restroom next door and said I wanted the key to the register - told him I wanted the money in his register, and he tried to get out. So, I hit him, then he kicked me, and we started fighting."

Prosecution witness Carol Brown Hinners testified that Helton told her in May 1969 that he had some keys he needed to get rid of and she told him she would take care of them for him. She testified that on another occasion Helton told her he had a fight with a service station attendant and took his keys. Hinners said she contacted the Fairfax Police in June and turned the keys over to them. On cross-examination, she testified that she hadn’t contacted Sohio about the $5,000 reward, nor had they contacted her.

On April 29, 1970, Charles Helton testified on his own behalf. He said he was “pretty high” on the night of the murder. He testified that he and Robert Mack had been drinking and driving around. He said they stopped at the station for gas. After he paid Troy Carr, he told him he was going to murder him. Helton said Carr came toward him and kicked him. A fight ensued and Helton said he threw the toilet tank cover at Carr. He said he proceeded to beat Carr with the cover. He said he picked up the keys from the ground because he thought they belonged to Robert Mack. As Helton left the restroom, he saw a customer at the gas pumps. He pumped the gas for the man and gave him change from his own pocket. He admitted that he had given the keys to Carol Hinners, but denied that he told her to get rid of them.

After eight hours of deliberation, on April 30 the jury found Charles V. Helton guilty of first-degree murder with a recommendation of mercy (which meant he wouldn’t face the death penalty). On May 1, Judge Wood sentenced Helton to life in prison.

Now the attention turned back to Robert Mack. On June 20,

1970, Hamilton County Juvenile Court Judge Olive L. Holmes ruled that Mack

should be charged as an adult in the Troy Carr case. Mack’s attorney Bernard

Gilday had wanted the case to remain in Juvenile Court so Mack’s sentence

wouldn’t continue beyond his 21st birthday.

On August 7, a Grand Jury again indicted Robert Mack for first-degree murder. On August 11, Mack entered a not guilty plea. Court of Common Pleas Judge William J. Morrissey ordered that he be held on $20,000 bond.

On December 2, jury selection began from a pool of 75

potential jurors. Ultimately, five women and seven men were selected.

Robert Mack’s trial began on January 14, 1971. Calvin Prem and Fred Cartolano again handled the prosecution. Deputy Hamilton

County Coroner Ben Yamaguchi testified that Troy Lee Carr died from a fractured

skull and hemorrhaging. Mary Carr identified the keys that had been taken from

the crime scene as her husband’s. In addition, the jury visited Snyder’s Sohio,

where the murder occurred.

Testimony on the second day of the trial largely focused

on the statement Mack gave to Fairfax Police on the day of his arrest. Bernard

Gilday objected to Calvin Prem’s admission of the statement into evidence, saying

that the State had not proven that the statement was made voluntarily. Gilday argued

that the arresting officers, Sergeants Paul Ferrara and David Planitz had told

Mack that giving a statement would make matters better for him and promised to

have the charge reduced to second-degree murder. Both Ferrara and Planitz denied

this on the witness stand. The statement was allowed into evidence.

Also taking the stand that day was Raymond Huber, who testified that a blood-splattered Charles Helton had pumped gas for him at the Sohio station.

Charles Helton testified that he and Robert Mack stopped at the Sohio station to get oil and then decided to rob it. They followed Carr into the restroom and told him it was a robbery. Carr told them to go home because they were drunk. A fight ensued and Helton testified that he picked up the toilet tank cover and threw it at Carr. He denied beating Carr with the cover, though he couldn’t explain why his skull was fractured and his throat cut. Helton testified that Mack stayed in the car for most of the robbery and murder and that Mack only joined in “to get Carr off my back.”

Robert Mack took the stand in his own defense. He said that his only involvement in the crime was trying to stop the fight between Charles Helton and Troy Carr. He sat in the car until he saw Helton and Carr walking toward the restroom and he got out to see what was going on. He saw the men fighting and said he pushed them away from one another. Helton hit Carr in the head with the toilet tank cover. The cover broke apart and Helton picked up a large piece and continued to beat Carr with it. After the beating, Mack testified that both he and Helton attempted to open the cash register, but weren’t able to.

Mack said that the night of the robbery and murder was the first time he had gone out drinking with Helton and that Helton was talking about "robberies and burglaries and stuff and said he needed money." He testified that around $25 was taken in the robbery and that Helton had given him $2 or $3 and instructed him not to say anything about what had happened. Mack said that he took off his bloody shirt and burned it at the side of a road.

Calvin Prem pointed out there were inconsistencies between Mack’s testimony and the statement he made to Fairfax Police on the day he was arrested. In his statement to police, Mack said he held Carr while Helton beat him with the toilet tank cover: "Charlie said he had seen our faces. I didn't want to hurt the guy. I told Charlie not to hurt him. I helped Charlie to hold him back. The guy was fighting. Charlie took the toilet thing and hit him." Mack denied these statements he made to the police.

In prosecution closing arguments, Calvin Prem recommended conviction of first-degree murder without a recommendation of mercy, which would result in a mandatory death sentence. Fred Cartolano said that both Mack and Helton went to the service station with the intent to rob it, so both were equally guilty of murder under Ohio law.

For the defense, Bernard Gilday said that Robert Mack was a "good boy and a clean-living boy who tried his best to prevent Helton from beating Carr." He said that Mack made a poor judgment that he couldn’t get out of. Gilday said that Mack had been under the influence of Helton, who was a member of a notorious motorcycle gang.

Arguments concluded on the afternoon of January 19, 1971 and the jury was sequestered overnight. After 12 hours of deliberation, on January 20, 1971, the jury found Robert Mack guilty of first-degree murder with a recommendation for mercy. Judge Morrissey sentenced Mack to life in prison. He would be eligible for parole in 20 years. Bernard Gilday entered a plea for a new trial, arguing that Mack’s statement to Fairfax Police should not have been admitted. He also questioned crime scene photos, saying that the body had been posed. Calvin Prem said that the court had already ruled on admission of the statement and that any photo of a dead body must be posed. Judge Morrissey denied the plea for a new trial.

No comments:

Post a Comment